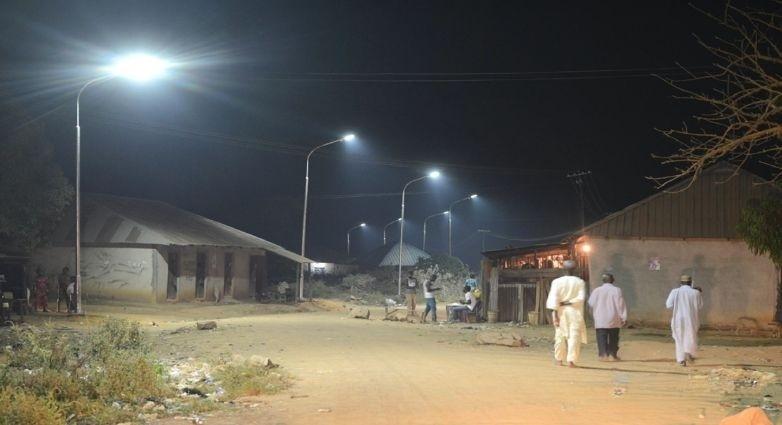

Nigerians are excited about the various solutions being proposed to address challenges in the power sector. Technological solutions once considered distant are now becoming the norm. As interest in providing off-grid and on-grid renewable energy solutions increases, a national debate has emerged about the unsustainability of the current reliance on fossil fuel power generation and the need to transition to renewable energy. However, what was missing in this conversation was the realization that these disruptive changes will only occur if we shift from a centralized grid model to a distributed renewable energy (DRE) approach. If the Nigerian Electricity Supply Industry (NESI) has learned anything over the years, it’s that an energy system without the early adoption of a well-planned energy mix is vulnerable to grid collapses caused by natural disasters and vandalism. The image above shows a rapidly deployable microgrid system, including solar, wind, and energy storage.

An energy system is considered distributed only if its production units are small, quickly deployable, and independent of a centralized power generation and distribution structure. There are three main types of electricity systems: centralized grid systems, mini-grids, and isolated systems. In many cases, mini-grid solutions (also known as microgrids) are primarily used to manage the energy supply and demand for a relatively small number of users (households, communities, and small businesses) within a local power network.

According to a 2014 study by Daniel Kammen and his team titled "Microgrids for Rural Electrification: A Review of Seven Case Studies," there are three mini-grid business models adopted by different developers: for-profit, partially subsidized, and fully subsidized models.

1. **For-profit model (FP)**: Developers rely on tariff collections to recover initial capital costs, cover operational and maintenance expenses, and ensure a return on investment. However, frequent energy theft can make the project financially unsustainable, requiring a robust energy management system and the use of smart meters by community users. This model tends to have unreliable energy services due to the lack of sufficient local training to reduce administrative costs.

2. **Partially subsidized model (PS)**: This model relies on subsidies for capital costs but depends on a tariff structure to efficiently recover operational and maintenance costs. Mild energy theft is expected, but a village power committee can be set up to manage customer relations and ensure that each household is metered. Local training is necessary for efficient management of these facilities. An example of this model is the 20kW mini-grid in Kigbe, Abuja.

3. **Fully subsidized model (FS)**: This model depends largely on government intervention and NGO-funded projects, providing less cost-reflective tariffs and minimal operational and maintenance provisions. The mini-grid project would require a concession process with an O&M contractor over a specified period, as outlined in the agreement between the contractor and the government. The reliability of energy services requires local training and the establishment of a village power committee to resolve conflicts. An example is the 40kW solar-powered isolated mini-grid in Gnami Community, Kaduna State, funded by the Federal Ministry of Power.

A combination of capacity shortages, insufficient energy services, prolonged bureaucratic processes, inaccessible remote areas, commercial banks’ reluctance to finance small-scale projects, the near-zero involvement of microfinance institutions, lack of data, grid expansion, and non-cost-reflective tariffs have all been major obstacles to mini-grid investments for rural electrification in Nigeria. However, with the recent formulation of a mini-grid policy by the regulator, which provides a structural framework to encourage financial institutions’ participation and attract mini-grid developers, increased rural electricity access and optimization of various energy sources are expected to spur the growth of MSMEs.

"My advice to all power developers is to focus more on small solutions that can be quickly deployed. We have issued a mini-grid regulation that allows anyone to deploy systems up to 1MW without a license." – Babatunde Raji Fashola SAN, Honourable Minister of Power, Works, and Housing.

According to the regulator's policy document, Nigeria's mini-grid structure is categorized as follows:

1. **Isolated Mini-Grid (ISMG) / Unserved Areas**: These areas are not designated to any Distribution Company (DISCO), and there is no existing five-year grid expansion plan by the DISCO. The mini-grid developer is allowed to construct, own, operate, and maintain the system with a NERC permit.

2. **Interconnected Mini-Grid (INMG) / Underserved Areas**: These areas are connected to a DISCO network but have unreliable electricity supply, with tariffs higher than the grid. The mini-grid developer, as required by the regulator, must sign a tripartite agreement with the community and the DISCO to construct, operate, and maintain the system.

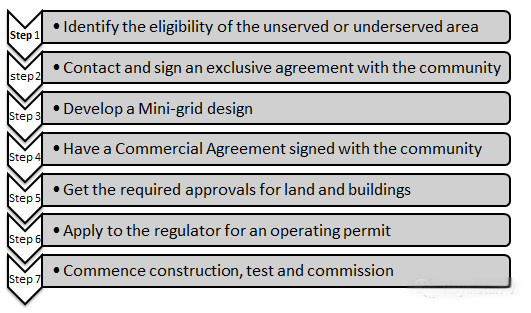

To attract reliable energy services and bankable mini-grid projects, the Rural Electrification Agency has outlined seven steps as the required procedure for developing a mini-grid project in Nigeria. A new dawn is breaking!

If you're interested in learning more about our solar energy storage offerings, we encourage you to explore our product line. We offer a range of panels and battery that are designed for various applications and budgets, so you're sure to find the right solution for your needs.

Website:www.fgreenpv.com

Email:Info@fgreenpv.com

WhatsApp:+86 17311228539

Post time: Oct-13-2024